I had the opportunity to share some thoughts at the International Mindfulness Conference 2024 in Bangor, Wales on a panel about "Contemplative, Philosophical, and Spiritual Approaches" alongside Catherine McGee and Nana Korantema Pierce Williams.

Here is my 12-minute talk about mindfulness and the value of looking at things from many different perspectives.

Transcript:

So I'm going to share a few thoughts and ideas that are inspired by my contemplative tradition of Jainism. And I also draw a lot on a project that I've been doing for several years called Just Looking. We're going to start with this a parable story which some of you might be familiar with. It's about the seven blind men and the elephant.

And so they're all standing at different places around the elephant and the one at the, at the tail end thinks that it's a rope and the one at the front thinks it's a snake, and so on and so forth. It's not exclusive to the Jain tradition, it also appears in, in kind of Sufi stories, Hindu stories, Buddhist stories.

But in the Jain tradition, it's used to make a really specific point which is about the importance of a concept called Anekantvad. So ekant means, uh, a single sided story, and anekant means not single sided story or many-sidedness. And it's kind of been a foundation for me in terms of how I approach my mindfulness work.

You might be wondering what this is:

This is a mycelium network that connects trees. And, um, over recent years, scientists have been discovering more and more about how these networks work, fungal networks. And, um, I mean, it's amazing the level of communication. They, uh, kind of exist intergenerationally.

Some of them have been around for 2, 400 years. Uh, they've been discovered and they also nurse each other in times of difficulty. So for example, if a tree was cut down and you just see the stump left, that stump could well still be alive for 50 up to a 100 years, just because the other trees are sending them nutrients.

And why am I telling you all of this in the middle of a mindfulness conference? Because the more I talk to you about this, the more it's going to shift your perspective. So say you walk past a tree stump tomorrow, with this thought in mind, you might look at it in a different way than you would normally. You might have a softer gaze, you might have compassion, you might be inspired by it in a way that you might not have without that information, without that story that I've just told you.

So the interesting thing about what we see, or what we look at, is we would assume that most of the signals are going from the eye to the brain. But in reality, there's far more signals going from the brain to the eye, because the brain's telling kind of a story about, about what to expect, what to see. And then information is gathered from the eyes to verify bits and pieces of that and to confirm. And so when you see something like this, you see the fence, you see the hands, a microsecond later you know it's gloves.

But you keep seeing it maybe as hands again and it's hard to differentiate and it's also kind of fun when your eyes play tricks on you. And some of the best ways of exploring this is to explore optical illusions, which I'm obsessed with. I've been collecting them since university days when I was 18. And this is the oldest one I've ever found.

It's in a temple in Tamil Nadu in India. And it shows a bull, if you look at it from this side, and an elephant, if you look at it from that side. And I don't know which one you saw first or whether you could see both, but now I've told you this, you can probably see them both and switch between them.

And, and that's fun, right? It just, It just loosens our sense of certainty about what we see. So my point is that actually what we see is easily nudged.

And if you've been watching the Olympics recently I've been watching the diving and within a day or two, I was noticing the subtlety of the size of the splash. It's just because that's what I was hearing from the commentators. And, so that's what you hone in on.

We're very easily influenced by why the people around us. This photograph is from the 90s. A photographer called Martin Parr, a British photographer, magnum. And he's just got a really fun eye.

Yeah, There's no denying that our perspective is easily influenced.

On a more serious note, I spent a lot of time in my 20s working on homelessness projects, and this is a project that was in New York called, making visible. And here you see this woman walking past and not noticing these two homeless people, but it was actually a setup.

So the two, the two guys, one of them's her brother, and the other is her uncle. And she has no idea because she hasn't looked at them, looked at their faces. And then afterwards the reveal, and she's like, "Aah, I just walked past these people!".

Our attention, prioritises certain information and deprioritises other information.

And that is the conditioning that, Catherine, you were talking about. And a lot of that is societal conditioning. That's not me, but it well could be in London. I do this despite my background working with homeless people and, truly valuing them and having spent hours conversing with them.

I often walk straight past because I'm lost in, my phone. And of course, when it comes to phones, it's not just the looking down, it's what we look at inside.

So this is a sneak preview of an illustration from my upcoming book. It's called Your Best Digital Life. It's coming out next year and it is very much about what we see, what we pay attention to, because the digital world is really an extension of our mind.

The algorithms that we find in our content feeds are now starting to follow us offline too. This is a billboard in Piccadilly Circus in London. where there's cameras embedded behind the screens to recognize who's looking at the screen. And then it adjusts for age, for gender, it looks at the length of hair, and then it'll show you an appropriate ad.

And so more and more, our worlds are becoming limited. There's a kind of attentional repertoire, a cliché and a bubble that's happening because of the personalization algorithms.

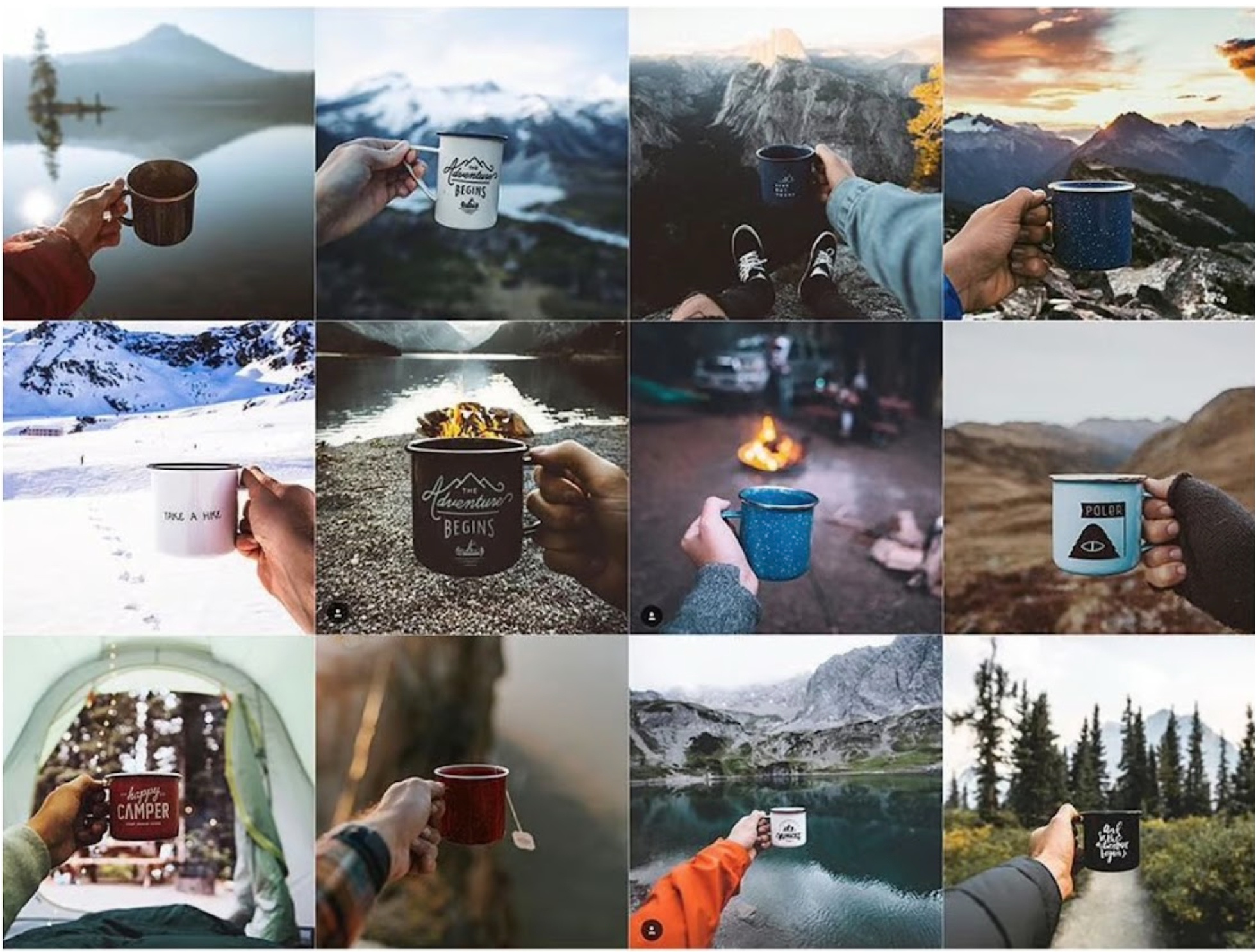

This is an Instagram feed called InstaRepeat, and what he does is he looks at various influencers, what they're sharing, and then puts them together. To make the point that we often just keep seeing the same thing.

And I mean, this is pretty benign, but say you go camping, you happen to have your coffee mug and there's a beautiful background. You may well just decide to take a picture of it. You notice it more because of all the things you've seen.

How to break this up?

Lots of eyes, because that's part of the, part of the answer is to have more perspectives, more stories.

So with the Just Looking project, we have developed a series of experiments in ways of looking to encourage, the noticing of things that aren't part of our normal repertoire, that no algorithms are pointing us towards.

So This is one of them. Every second, the Earth is rotating so fast. It's at the speed of four football fields, and yet we don't really notice gravity. Something like this, where you read this and you really let it, as Catherine said, let it really sink in, or rise up in you. And then you walk around on this earth and you get a sense of being, a small being on a blue rock flying around at high speed around the sun and, that'll lead to new kinds of connections and you'll notice new things.

Here's another one which I really love.

It's inspired by the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows. Each random passerby is living a life as vivid and complex as your own. Maybe we can we can try it for a second. Take a pause and look around and consider that the life of each person in this room is as vivid and complex as your own. You might notice a shift in how you feel about each other.

There's another interesting thing about noticing strangers is the white area around your pupil is actually much bigger in humans than it is in other primates. And scientists think that that's because it helps us to see where other people are looking. When you look at someone and their attention is on their phone or looking at an interesting thing in the sky, you follow their gaze much more easily, even from a distance.

And so we're that much more aware of other people's attention. Going back to this idea of, of what we notice is so easily influenced by others.

One more here which is very much connected to the Jain contemplative practice, this focus on impermanence. On some time scale, everything is fragile.

Tune in to this ephemerality. And again now looking around the room, maybe consider the building, consider the hill on which it stands, the mountains in the distance when you go for lunch.

It's all fragile. Again, having that story in your mind changes what you notice in the world around you. And this is not a new thing, obviously. People have been telling each other stories for eons. And this particular image is one of my heroes. Her name is Ganga Sati. She was a medieval devotional saint in India.

And here she's telling her daughter-in-law. She says "Mann ne stheer ker" Which means, "Still the mind"... "Aavo re medaan ma", which means, "And enter the playground." And what is she doing there? She's giving her a prompt. She's suggesting something pretty wild, which is beyond this body, beyond this mind. There's a whole world of things to experience, and she's drawing her attention to that based on her experience, whereas Paanbai, her daughter-in-law, has not yet experienced that.

But it opens the possibility. And this is my version of the Gangasati prompt, which I've written up, inspired by my own meditation teacher, and I often carry it around with me as a little card. Notice the silent awareness that knows your mind and lights up your senses. The beyond, the mystery and the potential wonder.

Going back to the elephant, the reminder of this elephant is that our experience of the world, what we notice is always going to be limited. So to embrace that, and that requires an epistemic humility, which doesn't come easy because we have to treat our own noticing with a certain kind of, what's the word I'm looking for?

A gentleness, and playfulness which is to know this is just part of the picture. And this concept of Anekantvad isn't actually about relativism of truth. It's not to say that, you know that, everyone's truth is subjective. This is actually about the possibility of wholeness. And that if we practice curiosity , we practice humility, we listen to other's stories, we stay open to the possibilities, we could see more, we could notice more. And that's the context that I bring this into the conversation about mindfulness is that if you were a mindfulness teacher standing there, when these people were commenting on what they see, we might well say, "good noticing!"

And it is good noticing, but there is more. And that's the possibility that I want to point towards. And I'll end with a quote from a Spanish philosopher, which is to do with the fact that at the end of the day, what you notice is the foundation of what you can connect with, what you care about and who you are... and what this life is for you.

And he says, tell me what you pay attention to, and I'll tell you who you are. It's a really important thing. Thank you.